Integration

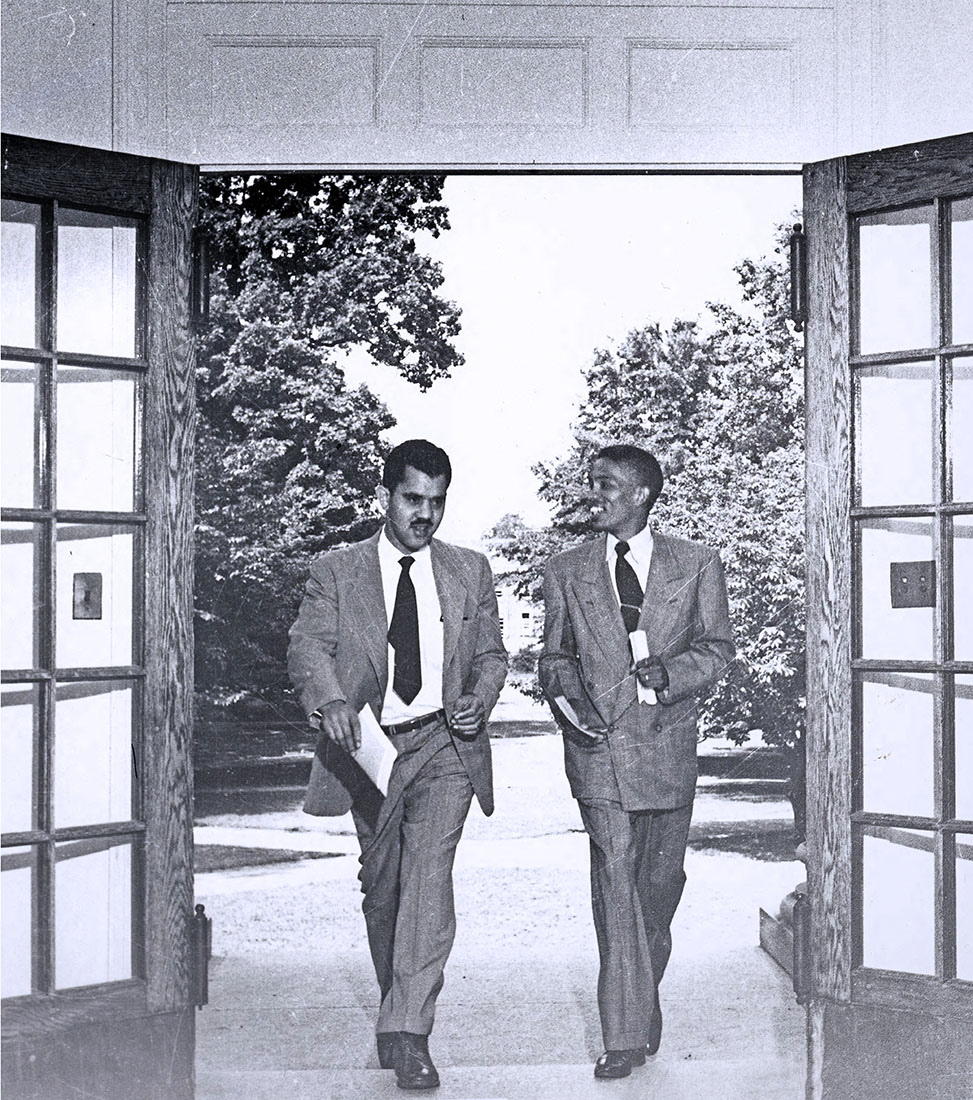

Under Jim Crow laws from 1900 to 1951, North Carolina's public schools at all levels were segregated institutions with separate schools for whites, African Americans, and Native Americans. In the 1930s university administrators successfully fought the entry of African Americans to graduate programs by helping open a law school and other graduate programs at the North Carolina College for Negroes in Durham (now North Carolina Central University). In 1951, however, in McKissick v. Carmichael, the courts ruled that the two law schools were not equal and ordered UNC to admit the African American plaintiffs to its law school. Following their legal victory, Harvey Beech, James Lassiter, J. Kenneth Lee, and Floyd McKissick enrolled in the summer of 1951. The same year Carolina admitted Dudley Diggs, an African American student, to the medical school because there were no comparable schools in the state, and Gwendolyn Harrison, a teacher, to summer school graduate courses.

Native Americans who sought entrance to UNC had a more arbitrary experience, as admittance sometimes depended on individual administrators. While there had been one or two American Indians in UNC programs in the 1920s, the 1950s court rulings also opened the doors to them. Cecil B. Lowry (Lumbee) entered as a junior in 1951, and the following year Genevieve Lowry (Lumbee) transferred to UNC as a junior and Otis M. Lowry (Lumbee) entered the medical school.

UNC continued to have a reluctant approach to integration. The first African American students were restricted to their own floor in Steele Dormitory (now Steele Building) and denied seating in the student section of the football stadium. Once the Supreme Court outlawed all forms of segregation in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the university had no further legal recourse. In the fall of 1955 the first African American undergraduates entered Carolina: brothers LeRoy and Ralph Frasier and John Lewis Brandon. Enrollment grew slowly; by 1963 only eighteen African American students were at Carolina.

Despite this step toward integration, local businesses continued to maintain racial segregation. In February 1960 nine African American high school students in Chapel Hill staged a sit-in at Colonial Drug Store, setting off years of boycotts, sit-ins, and marches. They were soon joined by university students from Carolina, North Carolina A&T in Greensboro, and other nearby colleges. Many clergy members, faculty, and town residents joined the protests. In March 1964 two African American activists and two white university students staged a weeklong Easter fast in front of the Franklin Street post office. The Ku Klux Klan responded by staging a rally in Chapel Hill. Student government generally supported the protests, and the honor court acquitted all of the student protesters who appeared before it. In contrast, the university administration, by far the largest employer in town, tried to maintain a publicly neutral stance despite its tacit support for segregation. The university's North Carolina Memorial Hospital still maintained segregated facilities, the university television station had refused to air a national program about desegregation, and the athletics program refused to move its weekly press luncheons from a segregated Chapel Hill restaurant. Passage of the Civil Rights Act in the summer of 1964 ended this phase of resistance to integration.

The university's first black athlete, Edwin Okoroma of Nigeria, joined the soccer team in 1963. Charles Scott became the first African American scholarship athlete in 1966 when Coach Dean Smith recruited him to join the basketball team. That same year, the School of Social Work hired Hortense McClinton, the first African American faculty member at Carolina.

Date Established: 1954

Date Range: 1954 – Present

Harvey Beech (left) and J. Kenneth Lee entering Manning Hall on June 11, 1951, their first day as law students at UNC. J. Kenneth Lee Papers, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library.